Displaced #10 – Mongolia

Evocative stories of people who have to leave their homes due to climate change.

The production phase of our DISPLACED project is coming to an end. The last trip has been completed and we are now in the middle of post-production. This is no small task with over 20 TB of data in the form of photos, videos, interviews, and audio files.

In just three weeks, the entire project will be on view as an exhibition at this year’s IPFO Festival at the House of Photography in Olten. Various print publications are planned for this fall, and a book publication is also under discussion.

As the work was created in close collaboration with the IOM (International Organisation of Migration) and WFP (World Food Programme), there are also plans to show it in their context, including at this year’s COP 30 in Brazil. However, the planned exhibitions in partnership with the UN still have a few hurdles to overcome, as the UN’s financial situation has deteriorated considerably since Trump came to power.

This work will certainly be on display in many different ways in many different places, and we will be happy to keep you updated on this.

Yours

Mathias & Monika

BRASCHLER/FISCHER

+41 79 205 0330

visualimpactprojects.org

CH40 8080 8009 0719 6376 6

Hellgasse 4 – 5103 Wildegg

Fifteen months after our first trip for DISPLACED, our last journey took us to Mongolia at the beginning of July. A country four times the size of Germany, but with only 3.5 million inhabitants. Half of these inhabitants live in Ulaanbaatar. As a result, this country is characterized by incredible, almost deserted expanses. Even during the early morning approaching flight, the vastness and solitude of the landscape was striking.

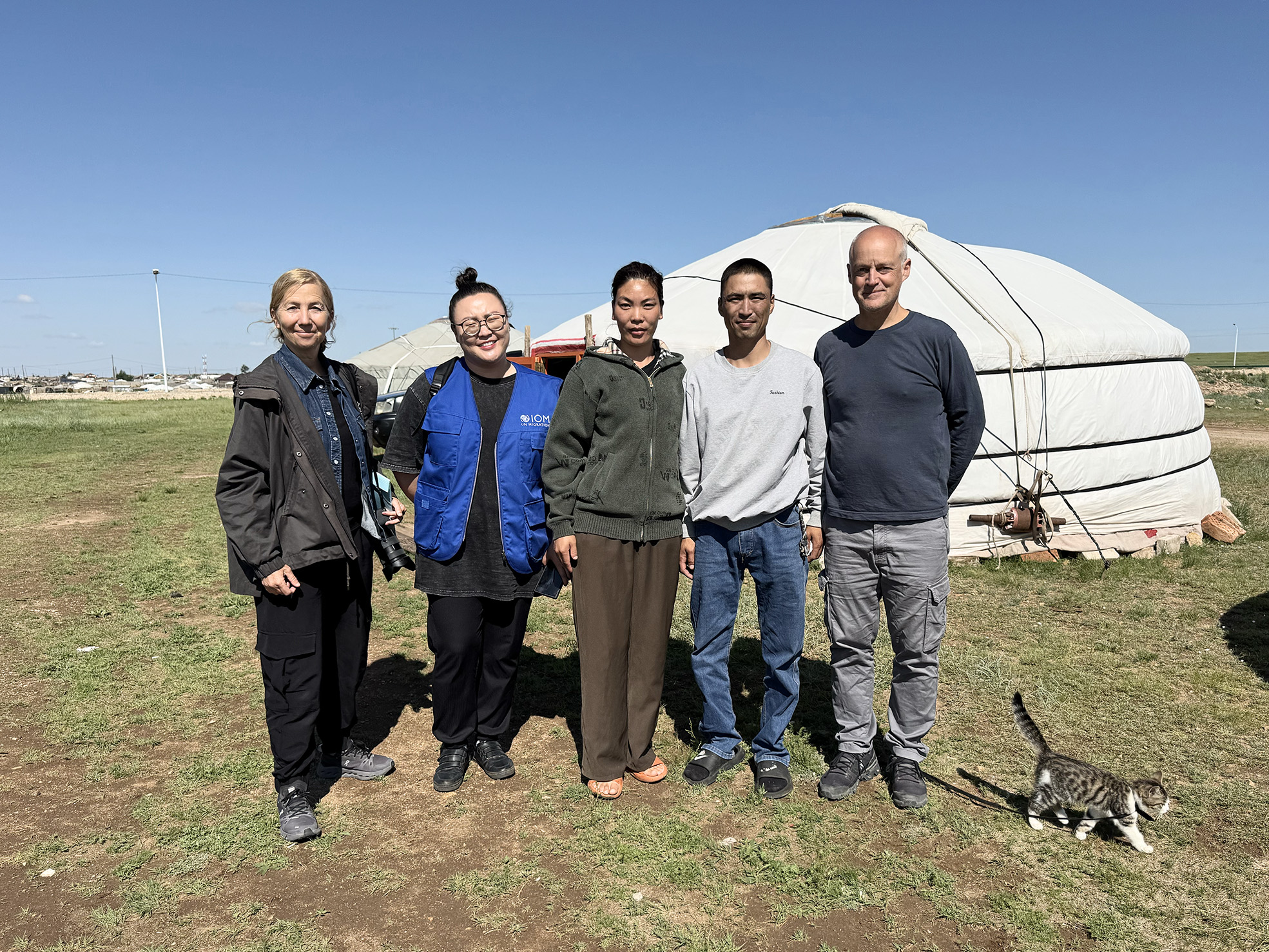

At the airport, we were met by Munkhtuya Davaajav, or Mya for short, who works for IOM Mongolia and would be our guide and translator for the week. On the very first day, after meeting with Daniel, the head of IOM in Ulaanbaatar, it became clear that Mya and IOM were doing everything they could to ensure that this would be one of our best-organized trips ever.

Mongolia has an extreme climate, and Ulaanbaatar is considered the coldest capital city in the world, with an average temperature of –2 °C. This is mainly due to the extremely cold winter months. In summer, when we were there, temperatures can rise to over 30 °C. This already extreme climate has become even more extreme in recent years. Climate change is having a significant impact on the country, particularly with the increasing frequency and severity of dzuds (harsh winters following dry summers), which in turn have devastating consequences for livestock farming and the livelihoods of herders. Mongolia has experienced a warming trend that is well above the global average, leading to hotter, drier summers and more extreme winter conditions. As a result, more and more nomadic herders are having to give up their traditional lifestyle and move to the cities.

On our second day, we met two former herders in Ulaanbaatar who now live in the city. The story of Otgonbat Yanjin is particularly tragic. Due to increasingly difficult climatic conditions, he gave up his traditional lifestyle as a nomadic herder and now works on an industrial chicken farm on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, living in an old minibus in the chicken farm’s parking lot.

While traveling around the Mongolian capital, we quickly realized that you need to allow plenty of time for this. It is not without a certain irony that Mongolia has one of the lowest population densities in the world, yet there is hardly any other place where you spend as much time stuck in traffic jams as in Ulaanbaatar. During the few days we were there, we spent an estimated 10 hours stuck in traffic jams. It didn’t help that the Emperor and Empress of Japan were on a state visit during our stay, which caused the already chronically overloaded transport network to collapse completely at times.

It was therefore convenient for us that on the third day we set off on our journey to Baruun-Urt, the capital of Sukhbaatar Province in eastern Mongolia. Google Maps told us that the journey there would take around eight hours. When we asked Mya about this, she simply said that it was nothing unusual in Mongolia. The long drive to Baruun-Urt took us through almost deserted, endless landscapes. The solitude was only interrupted by the white tents of the nomads and their animals, which were seemingly lost in the vast landscape.

The province of Sukhbaatar was hit by a particularly severe dzud in the winter of 23/24. Hundreds of thousands of herd animals died and many nomadic herders lost their livelihoods. Many of them moved to Baruun-Urt to find work there. However, most of them do not live in apartments, but continue to live in their yurts, which are called “gers” in Mongolia. As a result, entire ger districts have sprung up around Baruun-Urt. When we met former herders in the ger district, we were given addresses, but found that it was not easy to find the right tent in these informal districts.

Yanjmaa and Nerguibaatar were a young couple we had the opportunity to meet, and they shared their tragic story with us. They were both proud nomads who knew no other way of life. The devastating dzud began in October 2023, and the two recounted how the winter storms raged virtually without pause and more and more snow kept falling. Every day they fought for the survival of their animals, a battle they lost time and time again, as they realized each morning when they had to dig dead animals out of the snow day after day. In the middle of winter, Nerguibaatar released his 30 horses so that they could move around more and find food for themselves. It was a last desperate act to save what could still be saved. After the devastating dzud ended in spring, he set out to search for his horses. When he had to abandon the search after two months, he had only found four horses. The young family had lost their livelihood; only a handful of their more than 200 animals had survived. Today, Yanjmaa works as a nurse and Nerguibaatar as a security guard, and both dream of rebuilding a life as herders in the vastness of the Mongolian steppe. When we said goodbye to them, the couple gave us a homemade halter that had belonged to one of their deceased horses.

Most of the herders we met had no concept of climate change, but they could describe very precisely what had changed. This was quite different for Batkhuyag Namdan, who was a very successful herder together with his family in southern Mongolia. He owned sheep, goats, horses, camels, and cows—over 500 animals in total. But he too noticed that the climate was changing, even more so in his case, as he was moving around near the Gobi Desert. He began to study climate change intensively and came to the conclusion that his existence as a nomadic herder had no future. He and his wife Narangerel decided to sell their animals and move to the vicinity of Ulaanbaatar to settle there as sedentary farmers and engage in organic dairy farming. Today, the family has 10 dairy cows and around 100 goats and sheep, and still lives in two gers on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar. Batkhuyag is very happy with his new life, even though he cut off two fingers while repairing a machine four weeks before our visit. His wife Narangerel and his daughters process the milk into yogurt, cheese, and many other products, which they sell in their neighborhood. After the photo shoot with them, which was the last one of the project, we were invited to try their freshly made organic yogurt, which was fantastic, but unfortunately had unexpected consequences.

After an adventurous week in Mongolia, we set off on the long journey home to Switzerland. And there, unfortunately, after five days, we learned the hard way why you should be careful with raw milk products. First, Monika suddenly fell ill after a hike. She had headaches, nausea, and no energy. And a day later, Mathias started feeling ill too, but even more severely than Monika. Elias was not spared either, suffering from headaches and losing his energy. As Mathias’ condition worsened, he went to the doctor, where very high inflammatory markers were detected in his blood. He was immediately sent to the infectiology department at Aarau Cantonal Hospital. The doctor there was certain that we had contracted a bacterial infection related to the raw milk products we had consumed and immediately administered intravenous antibiotics to Mathias. Two weeks later, it is still unclear which bacterium is the culprit, as certain bacteria can only be detected in the blood after 20 days. As a result, the whole family is still on antibiotics. Although this is not the ideal conclusion to our project, it does have the great advantage that all the harmful bacteria we picked up on our adventurous travels have now been eliminated. And it seems that the raw milk bacteria were not the only culprits we were carrying inside us, as certain other complaints also disappeared with the antibiotics.